On jokes

Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. (The bomb is my sense of humor.)

I don’t suffer the delusion that I’m not a funny person. If you doubt it, all you have to do is ask my loved ones, who—each and every one of them and on more than one occasion—have had to wait patiently for me to deliver the punchline of a joke that I was laughing too hard to finish.

But I am not a funny writer. Or at least I’ve thought I wasn’t.

My attempts at slapstick felt careening and dissonant. (Part of which is due to the fact that for a long time, most of what I wrote was serious to a fault—of course slapstick felt tonally dissonant when the tone was mostly sepulchral.) Or I’d try for spry banter and end up with characters insufferably pleased with their own wit.

This is not to say that humor and seriousness can’t coexist! In fact, I think they should. My mentor and I actually had a great conversation about the usefulness of humor to not only counterbalance but actually magnify the emotional impact of—grief, anger, whatever. Some stories do it really well. Some are deeply compelling in most other aspects but fall just short of what they could’ve been with a little bit of levity leavened in there.

Humor doesn’t show the audience that you’re not taking your story seriously; it proves you’re taking it the exact right amount of serious. Which is to say, you understand that it’s the most necessary thing in the world and also it’s completely ridiculous. It’s fake! It’s made up! Laugh at it! While your guard is thus lowered a good story is taking the opportunity to turn your insides into the emotional equivalent of a handful of gravel run through a food processor.

So: take it as given that I want to leverage humor as just another available tool for writing. All well and good in theory. But what the hell am I supposed to do when I’m trying to write a joke for a culture that I haven’t finished inventing yet?

Wikipedia, obviously. I waded hip-deep into an article on Russian jokes, studying set up and punchline, trying to parse out what I personally found funny in humor based on historical references and cultural norms I was largely unfamiliar with. Drunk jokes? Pretty translatable, almost always funny. Some of the political jokes were deeply entertaining, once I could grasp the faintest nuance of context. But the first one that made me laugh out loud was a delightfully agile and morbid little thing that probably says as much about my relationship to ideas of nationalism and violence in 2022 as it did about the people who invented this joke more than half a century ago:

A man finds an old bottle, picks it up and opens it. The Genie comes out of the bottle and says: "Thanks so much for letting me out! I feel I should do something for you, too. Would you like to become a Hero of the Soviet Union?" (Hero of the Soviet Union was the highest Soviet award). The guy says: "Yes, sure!" Next thing he knows, he finds himself on a battlefield with four grenades, alone against six German panzers. (via Wikipedia)

So, taking away the historical context, why is this funny? For me, it’s the irony of getting something you wanted in a way you did not want at all. Violence looks different in the world of my novel, and so do ideas about nations/states/patriotism etc., but that irony translates.

Using this as a starting point, I ended up writing one of the scenes I’m proudest of (at the moment. I may re-read it tomorrow and be filled with irrational disgust, as is the writer’s curse). In a particularly solemn moment, Dumuzi and Jute are waiting for something Jute both wants and doesn’t want to experience. Dumuzi awkwardly offers a joke (spoiler alert: it’s about fish) only to be interrupted by the moment Jute was trying to avoid. Throwing the joke in there as an experiment let me (a) flesh out these two characters’ relationship in an odd but hopefully kind of endearing way, (b) have a serious moment arrive with more dynamism and impact, and (c) set up a quick little anchor for another character beat down the road. Voilà.

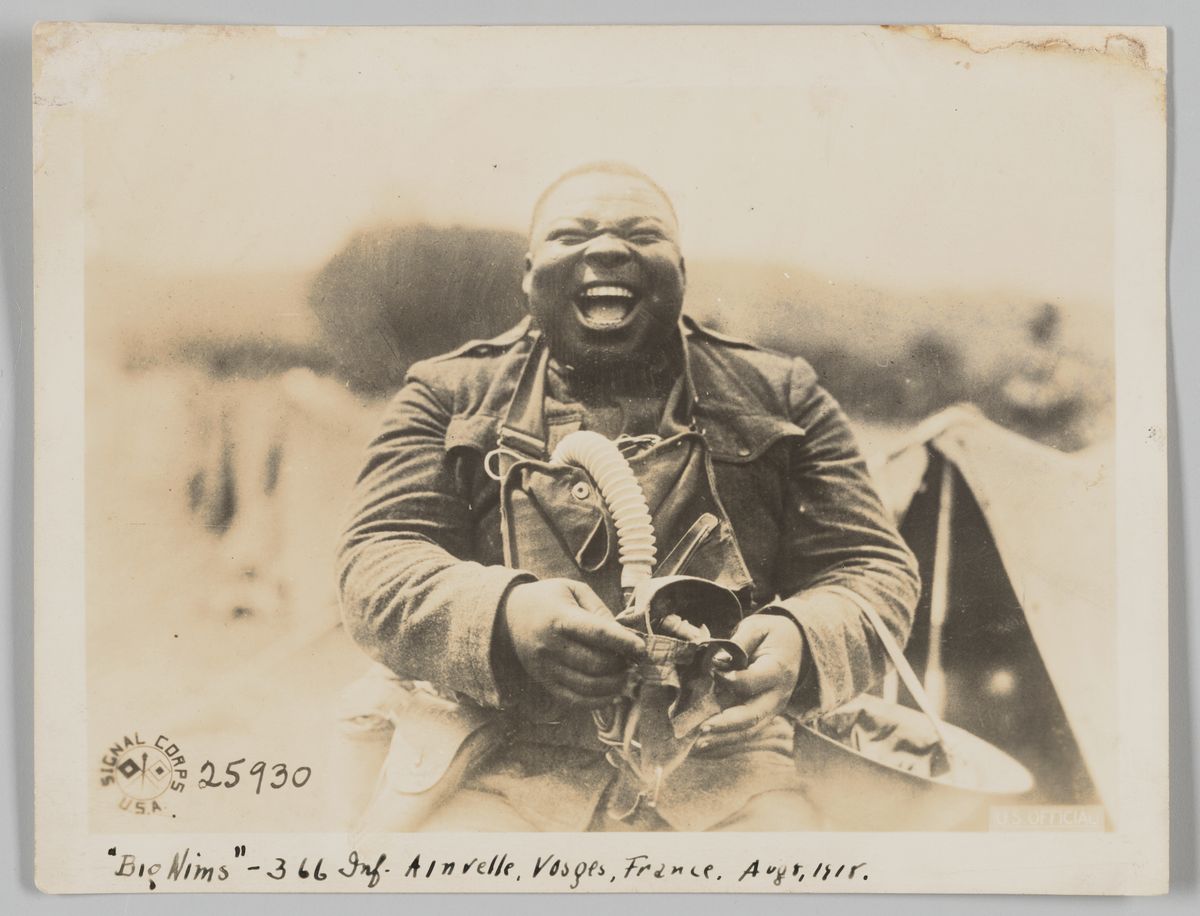

(Side note: I also want to point out how much war makes up a part of this post. Wartime header image, wartime joke. This was accidental, but I’m now calling it deliberate because I think it underscores the point I’m trying to get at: jokes land when they have counterweight. Counterweights have weight when there’s something lighter on the other side. All of which is basically just a step to the left of how I understand the poem “Motto” by Bertolt Brecht, who already said it cleaner and harder than I could.)

Anyway. Lesson learned? When the going gets tough, let the tough try joking. Besides, the best kind of story research is the kind where you end up watching Who’s on First? twice in a row because you were laughing too hard the first time through to hear half the punchlines.

Until next time, friends.

—Rachel/by the window/Tucson AZ/September 16, 2022

(the partial catalogue of cool, pt. ii)

- A New Yorker profile on @dril, the weird king of post-post-ironic humor

- Two tap-dancers bully an elocution instructor for laughs

- This live version of Hiss Golden Messenger’s “Heart Like a Levee,” where barely a minute in MC Taylor has to pause to commend the audience and they all laugh in delight

- The final bit of this Whose Line segment is the funniest thing that’s ever happened on Earth.