On weirdness

A great essay collection and an AI artbot help me figure out how to use weirdness as a writing tool.

A few weeks ago I went to the library to pick up my hold on Elvia Wilk’s Death by Landscape, a collection of essays about...pretty much most of the things I’m interested in, actually: bodies in nature, symbiosis and resilience, metahumanity and non-humanity, the nature of storytelling itself. (If she’d included a baseball essay I would’ve lost my mind.) This review in High Country News does a great job explaining why you might want to read it, so I won’t duplicate that work here. Instead, I want to talk about what this book made me feel about weirdness.

Specifically, it made me feel really really hype.

In my experience, kids tend to tune themselves in like freakishly sensitive Geiger counters to stuff that’s weird as soon as someone teaches them that such a category exists. It’s a nebulous threshold. I wasn’t being weird when I imagined myself as Batman at four-ish, but I was being weird when my friend and I made up Power Rangers stuff at six. Weird was good? Weird was BAD. Weird was irrelevant because I was spending sixteen hours a day in the library trying to finish my undergrad thesis. As I’ve grown, my personal experience of weirdness has charted a trajectory very similar to this Sarah Andersen comic:

All of which is to say, I thought I had a handle on it.

But Wilk doesn’t describe weirdness in a singularly social context, the way that I’d understood it for so long (because you only know what weird is when it bounces off of not-weird, which is an explicitly social equation). Wilk’s weirdness, on the other hand, is natural, mutable, and applicable—a tool of great utility in creating a certain kind of story in the pursuit of certain kinds of questions. Even stripped of moral judgments, weirdness is still an abstract. But if you look at it with a certain slant, it becomes something solid: something you can smack like a drum so that more weirdness will come echoing out. (Medieval female mystics were pretty good at this, it turns out—more on that in a later post.)

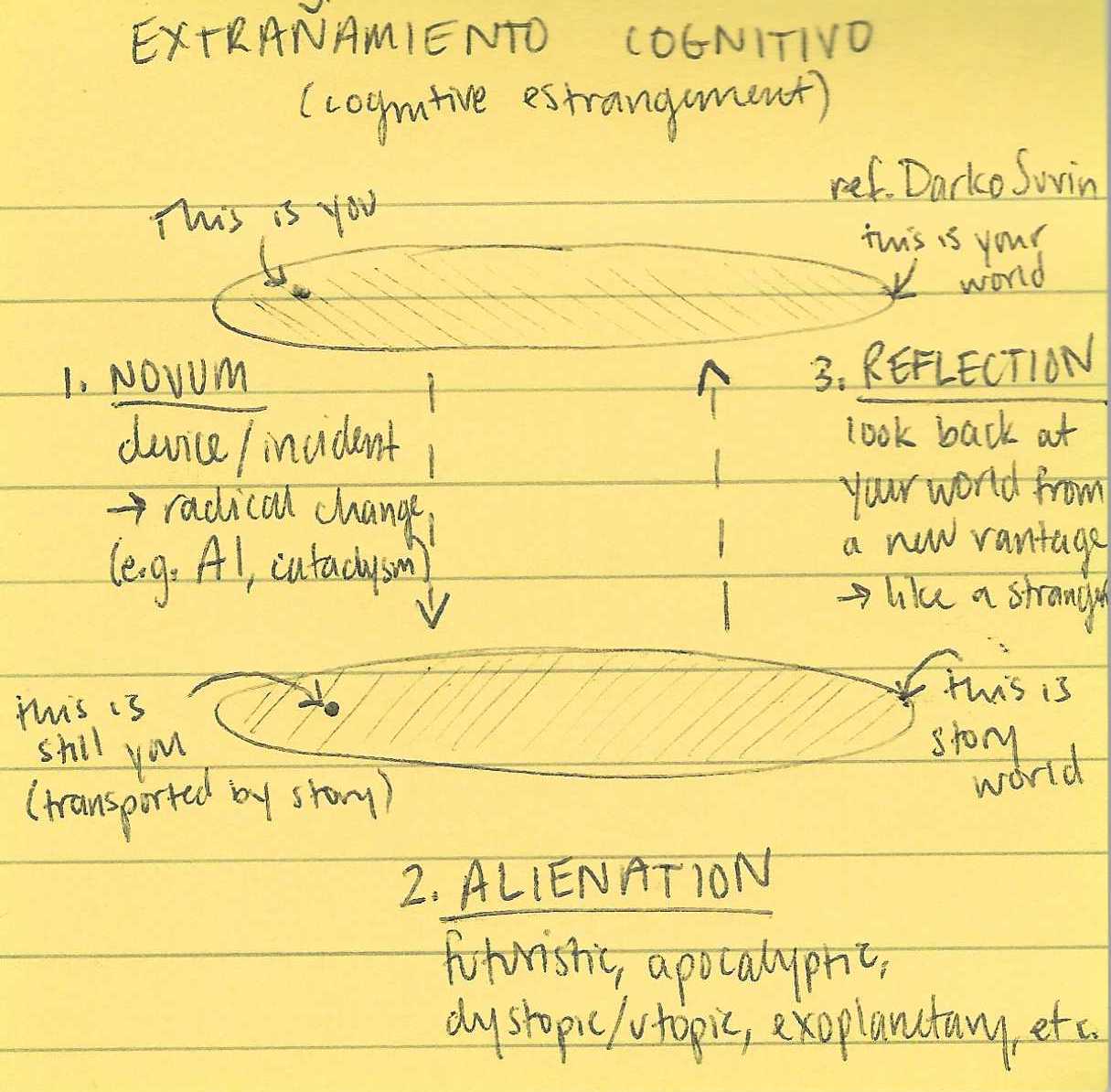

“[I]n new weird,” Wilk says, “I find a type of fiction that appropriates the capacity of old weird to estrange the familiar, but challenges its tendency to equate the unfamiliar with the freaky or frightening other.”

In other words, weirdness does what good scifi should: it makes the known world alien enough that it can be recognized anew (without trotting out poisonous human stereotypes to do so).

All this thinking on weirdness came at a point in the writing process where I was actually doing a lot of editing—exploding and rewriting chapters two and three to make a more solid foundation for the rest of the book in terms of plot logic and character motivation. In other words, I was at the perfect stage to be really deliberate about making it weird(er). I did this in a couple ways:

- I looked at places in the text I was having a really hard time editing. Why wasn’t I jazzed about it? What weird experiments—with tone, or dialogue, or action, whatever—could I do to bring life back into it? Did I want that moment to feel familiar, or strange, or both? Why? I didn’t give myself this kind of interrogation for every single word (dear God), but in spots where I was really stuck, it helped me get things moving in a new direction—which, more often than not, got me closer to where I wanted to go in the first place.

- I got hype about worldbuilding again, thanks to the artificial intelligence artbot Midjourney. Having had my socks blown of by some examples of its artistic capability, I dove in and started experimenting. In a day or two, I was producing illustrations of scenes or places I’d imagined in the book—except, because a weird and inscrutable machine made them, they were also very new and exciting! This process is helping me flesh out my own sense of the world I’m making, which is just awesome.

So, to sum up: I was able to break a weeks-long creative slump by being really deliberate and disciplined about the story research I was doing, which led me to two great and weird tools—Wilk’s book and Midjourney—that gave me buzzy new energy. Now on to the next stage!

Until next time, friends.

—Rachel/in the workshop/Tucson AZ/September 5, 2022

A playlist to accompany Death by Landscape

Instead of the normal catalogue, I’m sharing instead a little playlist of songs I felt were conversant with this particular book. You can listen to the whole thing here—I might keep adding stuff. In the meantime, a couple sneak peeks:

- Poliça, “Alive” // the lyrics are nearly impenetrable, which is a funny word for me to use once you look up what the singer’s saying; vibes with the chapter on compost

- Umbra Ensemble, “O Pastor” // a modern arrangement of an antiphon composed by Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179); the video is weird and excellent

- Susanne Sundfør, “Silicone Veil” // I picked just the one song, but this whole album is some of Sundfør’s flat-out best work